A Texan’s Reflection on Food, Tradition, and Innovation

A Texan’s Reflection on Food, Tradition, and Innovation

I could feel the friction between my cowboy boots and the hard Texas dirt as I walked past the rows of our family garden with feed in hand, ready to tend to the birds in the chicken run. The broilers were loud, impatient, and completely unimpressed that our whole family, including my doctor Dad and scientist Mom, made ourselves available to them every morning and every afternoon.

That was my childhood outside Boerne, Texas. Born on the Island (Galveston Island), my parents decided to settle into the Texas Hill Country after my dad became one of the earliest professors at the new University of Texas Medical School in San Antonio in 1969. We grew up collecting eggs, tending animals, growing garden produce and eating what we grew and raised when we could. It wasn’t a big operation. It was a small ranch-style property, the kind where you learn quickly that food doesn’t always “come from the store”—it often comes from work and a relationship with animals and dirt. We also spent an inordinate amount of time exploring the outdoors on foot and dirt bikes in our neighborhood with the friends that lived around us. My brother, sister and I were lucky enough to grow up before cell phones put an intoxicating and mesmerizing screen in ever person’s pocket.

Those early mornings left their mark. I’m an 8th-generation Texan with family roots that go back to when Texas was its own republic. I grew up in a place where beef isn’t a slogan. It’s history. It’s economy. It’s identity.

Texas Didn’t Inherit Ranching — It Built It

Long before “Texas ranching” became an image on a postcard, it was a practice imported and adapted. The Handbook of Texas traces the roots of ranching here to Spanish stock brought in as early as the 1690s, with ranching taking recognizable shape in the 1730s along the San Antonio River to supply missions and settlements. And for a long stretch of Texas history, cattle weren’t neatly contained behind fences. The Texas Historical Commission notes that from roughly 1700 to 1865, herds of Spanish cattle roamed widely, with the Texas Longhorn emerging as a descendant of that lineage. Hook ‘em Horns!

After the Civil War, Texas had millions of cattle, but not a lot of great ways to get them to market. Longhorns were plentiful, but unless a cowboy was fortunate enough to have nearby rail access (and there weren’t many railroads in Texas at the time), selling locally brought low returns on their investment. However, ranchers figured out that if they could move the cattle north and out of the state, they would get paid a lot more for their beef.

A livestock dealer named Joseph G. McCoy built stockyards in Abilene, Kansas in 1867. He encouraged Texas cattlemen to bring their herds to Abilene to be shipped east by rail. And thus, the cattle drive was born. Cowboys herded the cattle on the hoof – literally walking them from Texas to Kansas. That first year alone, tens of thousands of cattle reached Abilene, and the numbers grew massively as word spread. The network of routes used for those drives later became known as the Chisholm Trail, though historians note the name and its exact mapping evolved over time rather than existing as a single, clearly defined path.

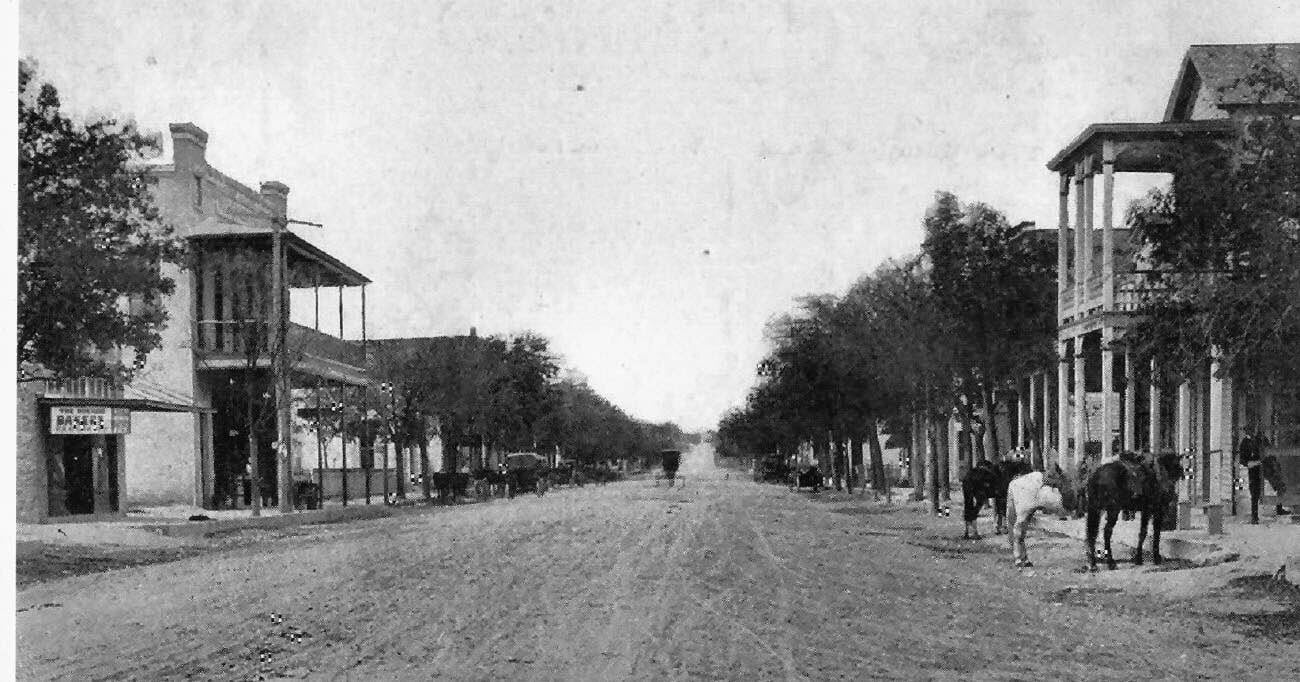

Boerne, Texas, 1890-1900. Boerne has a really wide Main Street, believed to be the result of needing lots of space for the cattle drives.

What was clear was the impact. Cattle drives helped revive the Texas economy after the Civil War. Cattle fueled the rise of cow towns like Abilene, Wichita, and Dodge City, and shaped what the world came to recognize as cowboy culture. For many families, ranching wasn’t just an occupation — it was a way to build a future through hard, uncertain work.

That era didn’t last forever. By the late 1800s, barbed wire, expanding railroads, and disease-control laws began to close the open range. But the decades that came before left a lasting imprint — not just on Texas’ economy, but on its identity.

The Present-Day Scale Is Still Staggering

This isn’t just “history.” It’s still an enormous living industry.

According to USDA NASS’s Texas Annual Cattle Review, Texas’ inventory of all cattle and calves was 12.2 million head on January 1, 2025, up from the year prior. So when Texans talk about cattle and beef, it’s not nostalgia. It’s a real economy with real people building real lives—often in conditions most folks never experience firsthand.

My Change Was Personal — Not a Rejection

Against that backdrop, here’s what may surprise people who know my roots:

Years ago, I gave up meat entirely. That wasn’t entirely choice. I nearly choked at least three times on meat, and one of those events landed me in the emergency room after an anniversary dinner with my wife. Today, my diet is mostly whole food, and plant-based, with an occasional bit of cheese and okay, I cheat occasionally with ice cream too.

My choice wasn’t about taking a swing at Texas, ranching, or the people who do it well. If anything, growing up close to land and animals has made me more aware of the tradeoffs that show up at scale—resource use, long-term sustainability, and the future we’re building for the next generation. Eating mostly plants is a personal decision. It’s not a purity test, and certainly not a lecture. I chose to put my health first, and it seemed to me that not choking on a piece of meat would be a great start to living a healthier lifestyle.

Then I Cooked “Steak and Potatoes” Again — Just Not the Way You Think

The plate I set recently looked like something I could’ve eaten growing up: steak and potatoes.

But the “steak” wasn’t beef. It was a plant-based whole cut from Chunk Foods.

Here’s what I can factually say about Chunk Foods (and what I can’t):

- Chunk Foods is a plant-based meat company founded in 2020 and based in New York, per company profiling with R&D operations near Tel Aviv, Israel.

- Their products are positioned as whole-cut alternatives (steaks, larger cuts, pulled-style products), and they emphasize versatility in cooking methods.

- Chunk states it uses eight recognizable ingredients and contains no gums, stabilizers, or preservatives (their words).

- Food industry reporting notes Chunk’s retail products contain vitamin B12, and lists ingredients such as cultured soy protein, coconut oil, fermented soy and wheat, beet juice, and fortified iron (among others), with protein amounts in the 25–37g range depending on the cut.

- Chunk’s own product page for its 6-ounce steak states 37g of protein and highlights pan-searing/grilling use.

- Multiple reports describe Chunk’s approach as using fermentation / solid-state fermentation to help create realistic “whole-muscle” textures.

Photo shot and food cooked by Me.

What I can’t fact-check as an objective claim is “it tastes exactly like meat,” because taste is subjective. What I can say is: to me, it hit a familiar note—especially in texture and how it cooked. Heck, I’ll go a step further. It was delicious. And I can’t wait to eat it again.

It browned. It sliced. It held together like a cut, not a crumble. And it let me sit down to a meal that felt like Texas—without me breaking the commitment I made years ago.

Why I’m Sharing This (And Why I’m Not Telling Anyone What to Eat)

If you make your living in cattle, you don’t need a tech founder telling you how the world works.

And if you’re a meat-eater, you don’t need a plant-eater telling you you’re a bad person. That’s not what this is about.

This is me saying: I’m encouraged when innovation respects what people actually love—familiar meals, real texture, real cooking methods—while also opening doors to reduce strain on land and resources over time. The value I learned on that small ranch property outside Boerne wasn’t “beef” or “no beef.” It was stewardship: take care of what feeds you, because you’re not the last one who’s going to need it.

Sometimes the future of food looks foreign. But sometimes it just looks like steak and potatoes.

Yum.

About the Author

Paul Adrian is the Co-Founder and CEO of latakoo. He believes fully in the power of journalism and the important role it plays in a functioning democracy. Adrian is the essence of a local reporter. As an investigative specialist, he covered the city hall beat, county commissioner’s court, state government, local businesses, the environment, countless disasters and hundreds of positive stories too in Texas, Ohio, Connecticut and Kentucky. He is an award-winning journalist who has earned multiple honors, including NATAS Emmy Awards for investigative reporting. He is a former member of the board of directors of the non-profit journalism organization, Investigative Reporters and Editors. After two decades of broadcast reporting, Adrian co-founded latakoo with Jade Kurian, and together, they used their extensive experience in the broadcasting and cable industry to successfully introduced latakoo’s video platform into some of the largest broadcasting companies in the world. Adrian holds a Bachelor of Journalism from the University of Texas and a Master in Public Administration from Harvard Kennedy School, where he focused on entrepreneurship.