Jade Kurian \ 15th July 2025

What We Learned Using Google Gemini’s AI Video Generator — And What It Means for Creatives.

At our company, we believe in testing new technologies. We always want to know if we can make our system more efficient. Since our inception, we’ve been at the edge of cloud computing, making media asset delivery and management as seamless as possible for users around the world. When we test new tech, we do it to understand what’s possible, what’s not, and what it means for both the community we create and the one that we rely on.

Recently, we ran an experiment: creating a marketing campaign using video generated entirely by Google’s new Gemini video tool. That meant no actors, no sets, no crew — just a prompt box and an AI model.

We didn’t do this to cut costs or because we think AI should replace human talent. We did it to learn, to think about the parts of this tech we can embrace and what parts we don’t want to adopt—and to share what we found to be hits and misses.

Great Prompts Don’t Guarantee Great Results

One lesson stood out right away, and it’s something most people already understand about AI: you must be painfully precise with your prompts. Yet even then, the AI often gets it wrong.

For example, I asked Gemini for a simple scene: a man working at a computer, filmed from behind so we don’t yet see that he’s half zombie. I even specified a side angle to hide the twist. The AI did the opposite—showing his zombie face immediately.

Example of an AI generated video

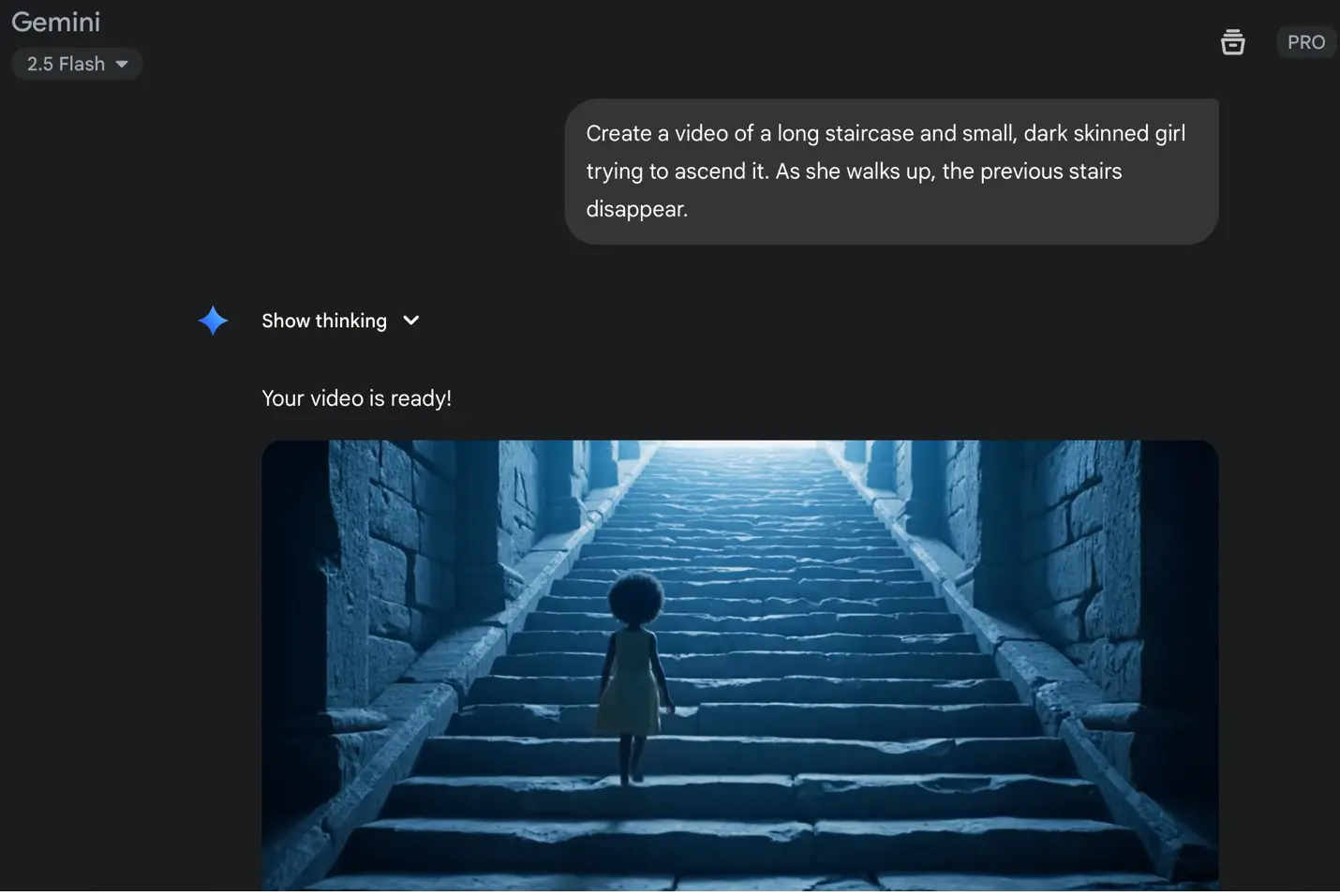

Here’s an example prompt: “Create a video of a long staircase and small, dark-skinned girl trying to ascend it. As she walks up, the previous stairs disappear.” The AI decided to make it magical by creating sparks where the girl stepped. Note that I didn’t request this. And the previous stairs did not disappear.

A human director would read nuance. An AI just does its best guess.

Audio That Repeats — Or Says the Wrong Words

Gemini can now add AI-generated voices—but in practice, they aren’t reliable. The voices in our test repeated words, skipped lines, or swapped them for something else, even when we provided a clear script.

Real actors pride themselves on knowing and delivering their lines.

Realistic Faces — But Flat Emotions

The visuals are impressive—faces look sharp and human at first glance. Spend a few seconds watching an AI face, however, and you’ll sense what we did: something is off.

Expressions can feel stiff or exaggerated. The eyes don’t quite move naturally. The tiny physical cues that show real emotion just aren’t there.

Welcome to the “uncanny valley” — when something looks human but not quite enough to feel real. The result? Viewers may disconnect or feel uneasy.

Actors spend years learning how to communicate feeling through micro-expressions and subtle movement. A machine can’t truly replicate that human nuance.

AI “actors” just look a bit off in their facial expressions and mannerisms.

Visuals Are Sharp — But Sometimes Too Perfect

Gemini’s video quality is undeniably crisp — high-resolution images, clean lighting, and vibrant colors. In some cases, they look better than stock footage.

But there’s a downside: AI visuals can feel too perfect. In the real world, light isn’t evenly distributed. Movements aren’t smooth. Scenes aren’t symmetrical. Real shoots have tiny imperfections — shifting light, subtle motion, and the natural messiness that makes a scene believable. Imagine “Glengarry Glen Ross” without the messy office or “Pulp Fiction” without, well, all the various messy scenes.

There’s also a serious question underneath all that perfection: Where are these faces coming from?

What We Know About How Gemini Creates Faces

Gemini’s video engine, called Veo, was developed by Google DeepMind. Veo is a “multimodal” AI model trained on vast amounts of text, images, and video. However, Google has not disclosed the specific datasets it used to train the faces and environments we see in generated video.

Independent experts believe it’s highly likely that Gemini was trained on public-facing web content, including stock image databases, YouTube videos, and face datasets like VGGFace2. These sources often include real people — sometimes without their knowledge or consent.

This matters because AI-generated faces can sometimes accidentally resemble real individuals — a phenomenon called “identity leakage.” Even if a face is synthetic, it might combine features in a way that reflects someone real.

And this isn’t just hypothetical. In early 2024, Google had to pause Gemini’s image generation of people due to racial and gender bias issues. The company acknowledged that the system was amplifying stereotypes and pledged to make adjustments before its re-release. In August 2024, Google reintroduced people in Gemini images, upgrading to their Imagen 3 engine. This update included new safety filters, watermarking, and restrictions to prevent photorealistic depictions of identifiable individuals, minors, and sensitive content.

Despite the guard rails and the stunning visuals, the lack of transparency about the images’ origins — and the known risks of real-person resemblance — raise ethical and legal concerns. As creators, marketers, and storytellers, we need to ask: Are we using someone’s face, even unintentionally, without their permission?

Only 8 Seconds — and No Continuity

As of now, Gemini only produces clips up to 8 seconds long. You can’t create anything longer, and there’s no way to keep the same “actors” from one scene to the next.

Even if you try to manually continue a story — same location, same character — Gemini treats each clip as a brand-new prompt. No memory. No continuity. No way to build a coherent narrative.

Example of a specific AI prompt giving different results

Commercial Use? Yes — But at Your Own Risk

Google’s current terms say that if you have a Pro or paid-tier account, you can use Gemini-generated content commercially.

But that comes with a major caveat: you are responsible for making sure you’re not violating copyrights, likeness rights, or other legal protections.

And because Google doesn’t disclose what datasets trained the model, you don’t know if the face in your ad resembles a real person. That creates legal and reputational risk, especially in advertising.

Bias, Deepfakes, and Disinformation

AI models reflect the data they’re trained on — and if that data includes biased, stereotypical imagery, the model will reproduce those patterns.

Ask for a “CEO” and you may see mostly white men. Ask for a “nurse” and get mostly women. Even neutral prompts can yield biased results. We found that to be especially true for the “Do the Flight App Update or Chance Zombie Apocalypse” marketing campaign video we put together using Gemini’s video capability. Any time that we did not specify someone with dark hair or dark features, the AI character was always a white person. Even if the character had ethnic features, their skin was white. We had to explicitly ask for “dark” or “brown” skin.

There’s also rampant misuse and abuse. These tools can create deepfake content that mimics real people or makes it appear someone said or did things that never happened. Case in point, recently Secretary of State Marco Rubio and the White House Chief of Staff were both impersonated using voice cloning. According to cyber experts, such cloning is becoming the norm. The risk of people being victimized by these tactics only increases as tools like Gemini become more powerful and accessible.

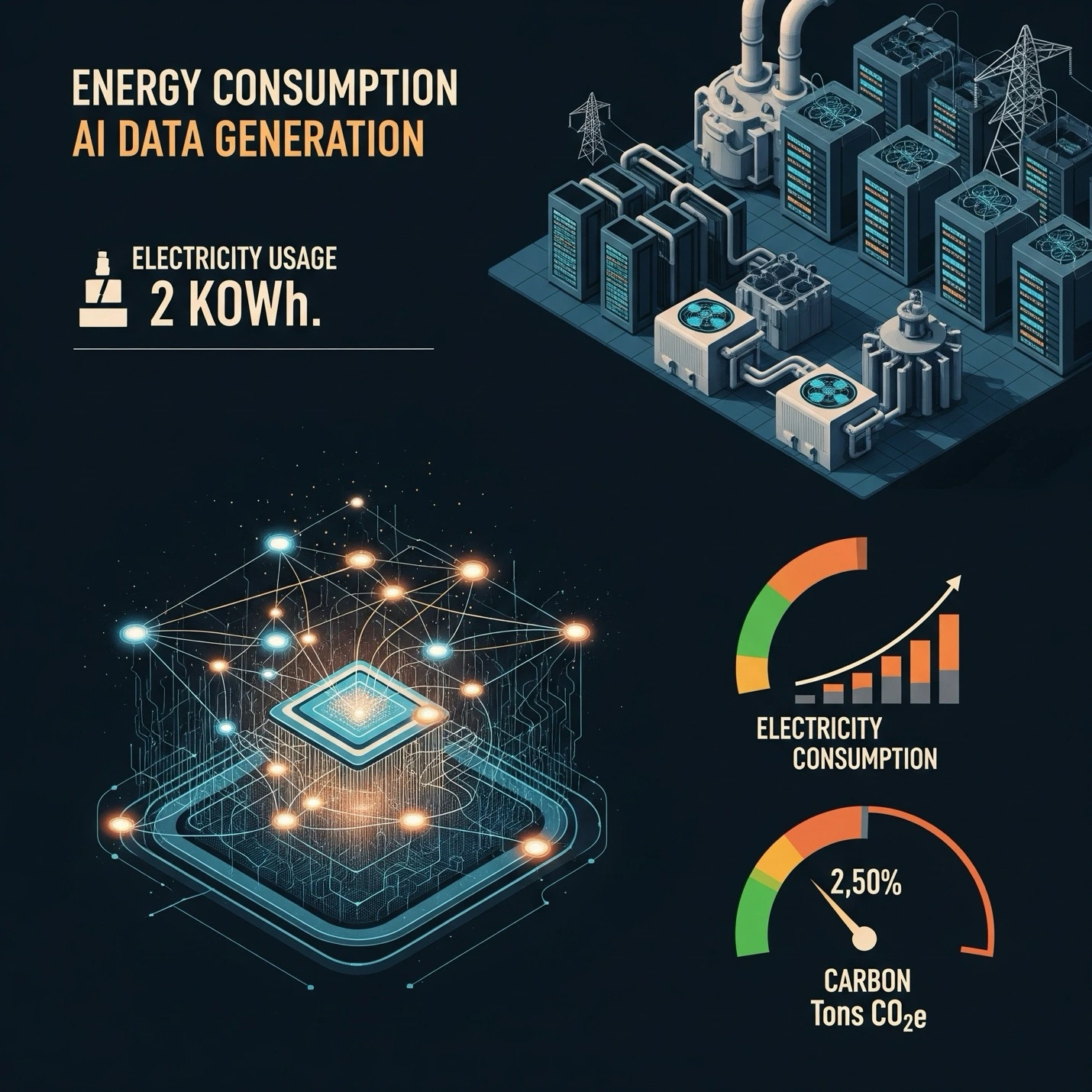

Environmental Cost — The Hidden Impact of AI Content

Behind every AI-generated video is a massive amount of computing power. Data centers, GPUs, and cloud infrastructure all require energy — a lot of it.

Researchers have shown that training a large AI model can emit over 626,000 pounds of CO₂ — the same as driving five gas-powered cars for their entire lifespan.

And it’s not just energy. Data centers also consume enormous amounts of water to stay cool. In 2023, Google disclosed that its AI expansion increased water usage by 20%.

So while an AI video may seem “virtual,” its environmental footprint is very real. The resource cost of AI is anything but artificial.

What Happens to Real Creatives?

This is the part we wrestled with most.

If AI can generate stock-like video — fast and cheap — who gets left behind? The first wave isn’t movie stars. It’s working actors, voiceover professionals, writers, editors, camera operators — the freelance creatives who power everyday content.

During the 2023 WGA and SAG-AFTRA strikes, AI protections were a key issue. Unions demanded guarantees that the studios wouldn’t scan actors’ faces or voices and use them indefinitely without consent or payment.

Meanwhile, companies like Google, OpenAI, and others have lobbied for relaxed copyright rules, allowing them to scrape data from across the internet to train their models — often without compensation or consent. The Trump administration is also supportive of less regulation over AI.

To be sure, there’s no simple answer here. But there is a responsibility to be transparent, thoughtful, and fair. If your video campaign is built using AI that mimics a real person’s likeness — should that person be credited or paid? These are the ethical questions brands need to develop answers to.

The Efficiency Factor — Why Marketing Teams Are Paying Attention

Here’s the reality: we were able to produce this campaign with just one person on a laptop typing in prompts and another person editing the AI generated videos.

No casting, no location scouting, no gear rentals, no additional payroll. In under an hour, I had several branded videos to test in-market.

That’s incredibly efficient — and appealing for small marketing teams or startups with limited budgets.

AI video reduces friction in production. For simple concepts, prototypes, or internal drafts, AI can save time and money. But those same efficiencies are exactly what threatens creative labor — and that’s why it matters how we use them.

Here’s our finished fully AI generated video for our Update Your Flight App campaign.

Where We Stand

Our campaign wasn’t an attempt to replace people. It was a test — a snapshot of where AI video stands today, what it can do, and what it can’t.

The technology is improving, fast. But it still can’t tell stories the way real people can. It lacks continuity, emotion, nuance, and context. AI may be able to simulate human faces — but it can’t feel or connect the way a real actor or storytelling team can.

As a company, we believe creatives should be paid, credited, and protected. And while AI tools can offer powerful efficiencies, they must be used ethically and transparently. We are not abandoning real actors and storytellers or AI generated videos. But we will put a great deal of focus on what types of videos we create with AI based on how our decisions impact both people and our natural resources.

About the Author

Jade Kurian is the Co-Founder and President of latakoo. She has experience in multiple facets of broadcasting and technology, including management, communications, sales and marketing. Jade is a patent holder. She understands video workflow: codecs, formats, editing, transfer. During her broadcast career, she worked in the field as a reporter/anchor, produced news shows and content, managed staff, coordinated crews while traveling the world. Jade launched and managed the ground-up building of a news bureau for a national network. She currently runs operations for latakoo and helped to build the team and systems that latakoo runs on.